Coming from the U.S., where strict aesthetic guidelines shape entire neighborhoods, and zoning laws seem designed more for preserving political turf than fostering creativity, discovering Japan’s approach to urban development completely blew my mind.

In America, minimum lot sizes, rigid zoning, and design review boards fill our suburbs with oversized, siloed districts. Want to build a small, smart, weird little house in your backyard? Good luck.

It often feels like local municipalities enforce aesthetic sameness not out of a shared vision but out of fear. Fear of change, of density, of a sore thumb.

Europe’s not much better. Despite its charm, it leans heavily into preservation, with landmarked districts and architectural uniformity dominating the urban core. (And I’m not arguing against landmarking just pointing out its unfortunate tradeoffs, I do love some beautiful European city squares)

So when I started learning about Japanese zoning and building culture, it was like the fog lifted. Japan’s system isn’t just different, it’s radically more democratic, more human-scaled, and honestly, more fun.

Post–World War II Japan is where this story really begins. After the war, the country was devastated. Entire cities were flattened. Millions of Japanese soldiers were returning home, and housing was scarce. In rebuilding from scratch, Japan made some unorthodox and, in hindsight, genius decisions.

First, and perhaps most profoundly, Japan never enacted an aesthetic ordinance for housing. That might seem minor, but in the West, aesthetic controls are what keep neighborhoods “cohesive.” In Japan, they let it go. Maybe they were too focused on housing people quickly, or maybe the existing urban fabric was so thoroughly destroyed by bombing that there was no “old look” left to preserve.

Either way, it opened the door to one of the most creatively diverse domestic landscapes on the planet. In Tokyo today, you’ll see Bauhaus-inspired boxes next to neon-trimmed futurist homes next to weathered wooden townhouses, and somehow, it works.

Even the way homes are addressed in Japan reflects this rejection of adjacency. In the U.S., your address reflects your place on a block. In Japan, homes are often numbered based on the date they were built, not their position relative to neighbors. Your home isn’t defined by what’s next to it, it stands alone.

Second, Japan’s fire codes unintentionally supported this freedom. Because of the country’s long history with devastating fires, regulations required firebreaks between structures.

So, homes in Japan are almost never touching. This makes demolition and rebuilding easy and common. Combined with the cultural preference for newness over heritage, many homes are built with the assumption they’ll be torn down in 30 years.

That frees homeowners to design homes for themselves, not for resale. If you know your house isn’t forever, why not make it something bold, personal, maybe even a little strange?

Third, there’s no minimum lot size. After the war, high inheritance taxes encouraged families to subdivide their land into smaller and smaller pieces. That gave rise to the skinny, quirky micro-lots we see all over Japanese cities. And yes, these sites are tight, but for architects, they’re pure creative fuel. Designing for a 20-square-meter footprint might sound like a constraint, but in Japan, constraints are where the magic happens.

The only real national regulation that guides residential form is Japan’s sunshine laws, which protect your neighbor’s access to sunlight. You can build high, but not if you block out the sun.

In a way, that single rule speaks volumes about Japanese values: individuality is allowed, even encouraged, so long as it doesn’t hurt someone else’s quality of life. Imagine applying that logic in the U.S., where even a modest backyard ADU can launch a full-blown zoning war.

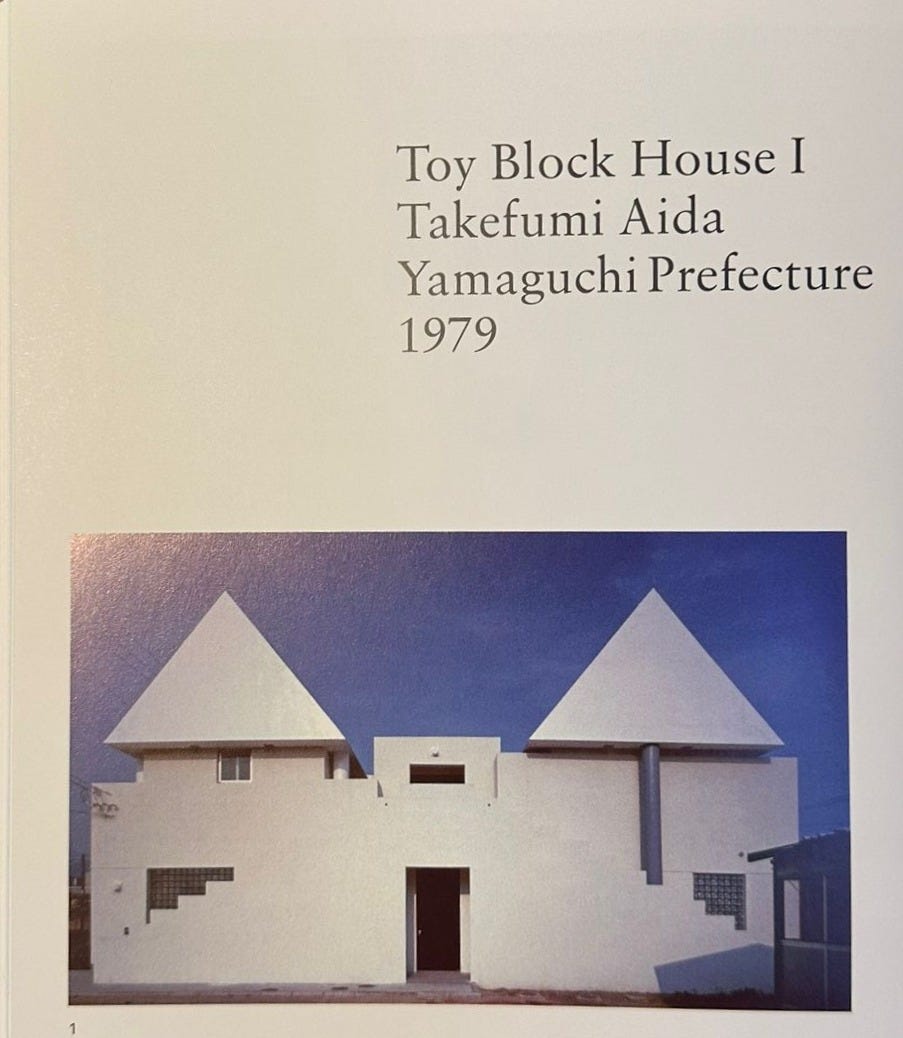

Naomi Pollock’s The Japanese House does a beautiful job tracing this history, not just through policy, but through the evolution of design itself. The book is packed with fascinating case studies and small insights that highlight how Japan turned rebuilding into a cultural renaissance.

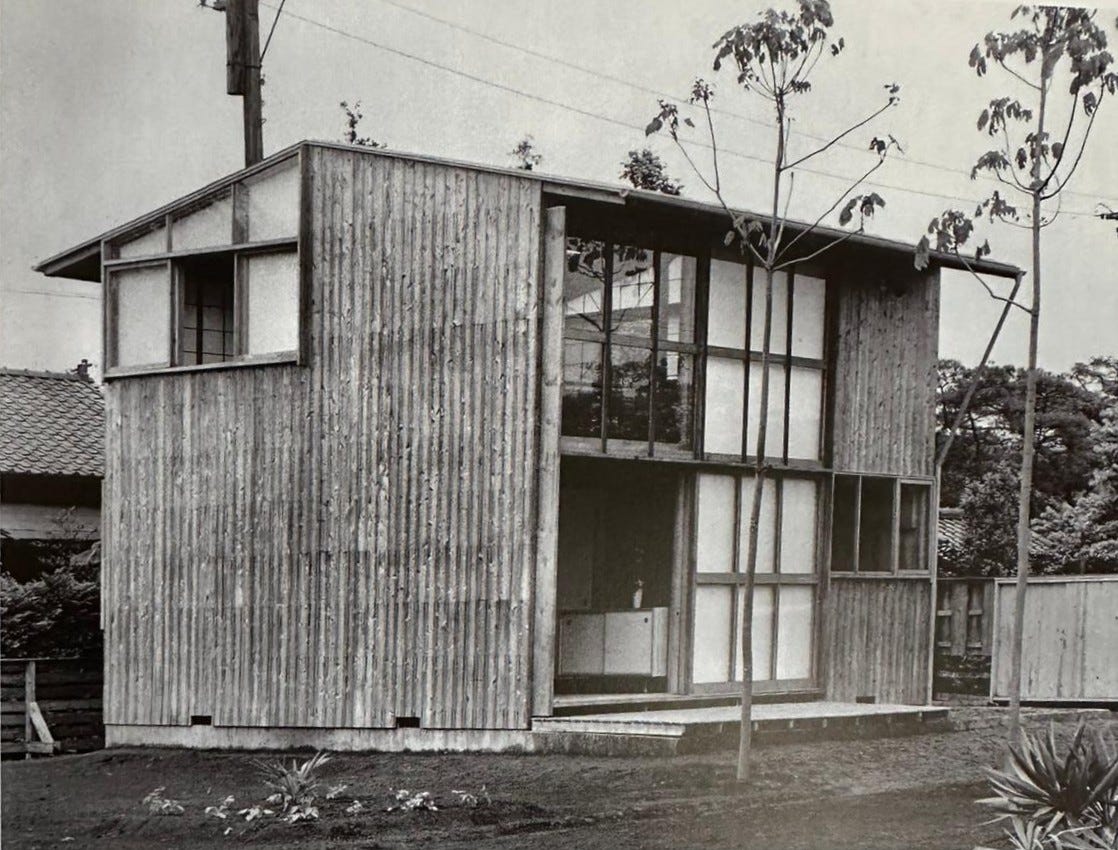

One of my favorite homes in the book is Minimum House, designed by Makoto Masuzawa. After the war, the Japanese government set a maximum construction size of 538 square feet (50 square meters) in an effort to quickly meet housing needs. That limitation sparked a wave of ingenuity. Minimum House is simple, elegant, and efficient, with large sliding shoji screens that blur inside and outside, privacy and openness, utility and beauty. The home may be small, but it breathes.

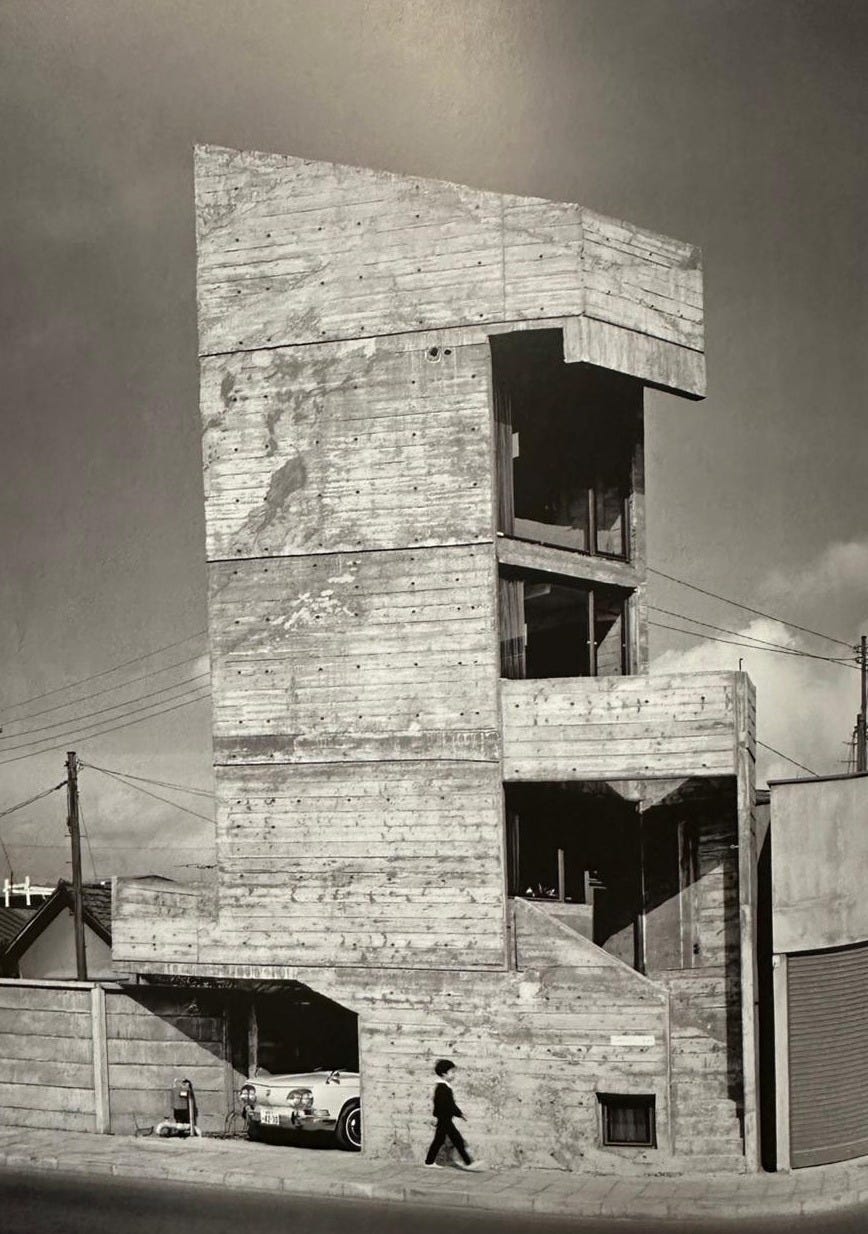

Then there’s Tower House by Takamitsu Azuma, a four-story vertical home built on a 20-square-meter lot in central Tokyo. It’s only 700 square feet total, with one room per floor: a basement office, a living/dining/kitchen above, a bathroom, a bedroom, and, at the top, the daughter’s room. The staircase winds organically through the space, and there are no doors. Each level feels connected by sound and presence rather than walls.

The book includes a short essay by Azuma’s daughter, Rie, who describes how the home shaped their interactions. “Each one of us felt the presence of others in the house, which shaped our interactions and revealed something specific and essential about the way we communicate in Japanese culture.” I found this especially striking.

I grew up in a house where privacy was sacred, where closing the bedroom door meant “respect his space.” But in Japan, and even in my own home in Otaru, privacy feels like a shared understanding, not something enforced by architecture. You’re always aware of the people around you. And that closeness, even with its challenges, can be beautiful.

I used to fantasize about turning an abandoned concrete silo in northern Vermont into a tall, narrow house. Something quirky and vertical with a room on each level. Tower House made me realize that idea isn’t far-fetched, it’s very Japanese.

So, why is Japan a dream for architects?

Because it trusts them. It gives them freedom. It gives citizens freedom. No design review board telling you your eaves are too wide. No zoning code killing your vision before it begins. Just a set of loose, sensible rules designed to protect quality of life, not to enforce sameness.

In Japan, building a home isn’t about following a template. It’s a personal expression, a cultural dialogue, a design challenge. Every home tells a story, and together, they create cities that are layered, weird, and wonderful.

If you're an architect, or just someone dreaming of building something that's truly yours, Japan is the place to be.

Check out our new FREE search and discovery tool. Nipponhomes

Take the Next Step

Join our community for exclusive insights and resources on Japanese real estate investments.

Our team

Meet the founders.

Derek has been working in the Airbnb space for the past 10+ years and recently purchased a home in Japan. He is excited to bring this investment opportunity to others in the States & abroad.

Nick has a passion for adventure and has always dreamed of owning a property in Japan. His dreams finally came true when Derek brought him in on a deal of a lifetime in Hokkaido, Japan - one of Nick's favorite places on Earth.